Stoker 1st Class WILLIAM ERNEST HERBERT NEWBY

1, Ashley Terrace, Winchester (no longer stands)

Service number K/16532, HMS Queen Mary, Royal Navy

Killed in action, Battle of Jutland, 31 May 1916

Family Background

William Ernest Herbert Newby – known to family and friends as Bert - was the youngest child of John and Annie Eliza Newby (née Bailey) and was born at Kilmeston, near Cheriton, Hampshire, on 12 July 1892. His father was born in London in about 1853 and by 1871 was working as a labourer and lodging in Shipton, near Andover. (John’s mother was from Shipton which might explain why John was there in 1871.) Bert’s mother was from Sherborne St John, near Basingstoke, Hampshire, and she was about 35 when she gave birth to him.

Bert had three older siblings: Edward John had been born in Andover in 1876, Elizabeth Annie, whose birth was registered in Winchester in 1878 and Maria Lucy who was born in Hursley, near Winchester, in 1882. These different birthplaces reflect the family’s peripatetic existence, presumably driven by where John Newby could find work. In the 1881 Census, he was listed as an agricultural labourer in Hursley and the family’s address was ‘the Sheephouse’. However, ten years later, and by then living in the village of Kilmeston, John’s occupation was given as an engine driver on a farm. The Newby’s eldest child, 14-year-old Edward, was listed as a shepherd.

By 1895, the Newby family were living at 40, Wharf Street, Winchester. This property, which faced up the hill towards Chesil Street, was demolished in 1974 to make way for the residential development of Wharf Mill. By 1899, the Newbys had moved to 33, Eastgate Street, Winchester. This has also been demolished and was at the top of Eastgate Street which at that time came out at Durngate Place by The Willow Tree public house. No. 33 would have been opposite the pub in what is now Durngate Terrace.

In the 1901 Census, John Newby was an engine driver (stationary). Perhaps there was more opportunity in an expanding city for that skill rather than in the countryside. However, his wife Eliza was listed as a charwoman so there was perhaps still a need for extra money. Their son Edward, aged 24 and living at home, was working as a carman or carter for railway agents. Lucy Newby, aged 18, who was also at home, worked as a shop assistant at a stationers while eight-year-old Bert was at school.

In 1900 Bert’s elder sister, Elizabeth, married Frederick Padwick, a brewer’s cellar man. They lived at 101, Upper Brook Street where their only child Lillian was born on 2 November 1900. Sadly, Elizabeth died in 1903, aged only 25. At this stage George and Lillian probably went to live with his parents in nearby Middle Brook Street as a ‘G. Padwick’ only appears in Warren’s Directory from 1901 to 1903. The 1911 Census supports this theory as it shows Frederick and Lillian living at his parents’ home at 58, Lansdowne Terrace, Middle Brook Street.

Shortly after Elizabeth’s death, Bert lost his father John who died in Winchester in 1904, aged only 52. His mother stayed on at 33, Eastgate Street, almost certainly with Bert as he was only about 13 at the time. Bert’s older brother Edward and second sister Maria also probably remained at the house. In 1906 Maria (under the name Lucie Marie Newbie) married Alfred Stewart Meldrum in Winchester. By that time, Annie Newby was living at 10, Sussex Street, Winchester (No.19 today), presumably with Bert, who was then 13 and due to leave school, and possibly with Edward.

The year 1910 saw two weddings in the Newby family. First, Bert’s widowed mother Annie married Charles Frederick Goodenough, a 51-year-old widower, whose first wife had died in 1904. Charles had been born in Winchester in 1859 and worked as a hire carman (carter). In the 1890s the two families had both lived in houses just a few doors apart at the top end of Eastgate Street, although their residencies only overlapped by one year – 1899. Bert’s brother Edward also married in 1910. His wife was Mary A. Simpson and the couple married in Reading.

In the 1911 Census, the two pairs of newlyweds were both living at 22, Nuns Road, Hyde, Winchester, Charles Goodenough’s address before he married Annie. Interestingly, on the census forms they were listed as two separate households, rather than Edward and Mary Newby being designated as visitors or relatives. Their census record allots them two rooms each, apart from the kitchen and any washing and toilet facilities which were presumably shared. Bert was with his new stepfather and mother, who was listed as ‘deaf”. Both Charles and Bert were ‘workers’, i.e. employed by someone else, but worked ‘at home’. Charles and Edward were still ‘carmen’ while Bert was working as an apprentice for a hot and cold water fitter. It seems he had inherited his father’s practical skills.

19, Sussex Street, Winchester, where young Bert Newby

was living with his mother widowed Annie in 1906.

The house was then No.10

22, Nuns Road, Hyde, Winchester, Bert’s home in 1911

after his mother remarried

Edward and Mary’s daughter, Violet Elizabeth (known as Bessie), was born on 19 June 1911. As Edward Newby does not appear in Warren’s Directories as a householder, it is probable that the two households remained at 22, Nuns Road with Charles continuing as the named householder. However, none of Charles’s five children were living with him. They were all old enough to have left home.

Early military Career

Bert Newby enlisted with the Royal Navy as a stoker on 9 October 1912. He signed up for 12 years - five in active service and seven in the reserve. He gave his occupation as a whitesmith, a person who makes and repairs items made of tin. His motives for joining up will never be known. Perhaps it was the practical and mechanical side that appealed to him or a desire to get away from home and see the world?

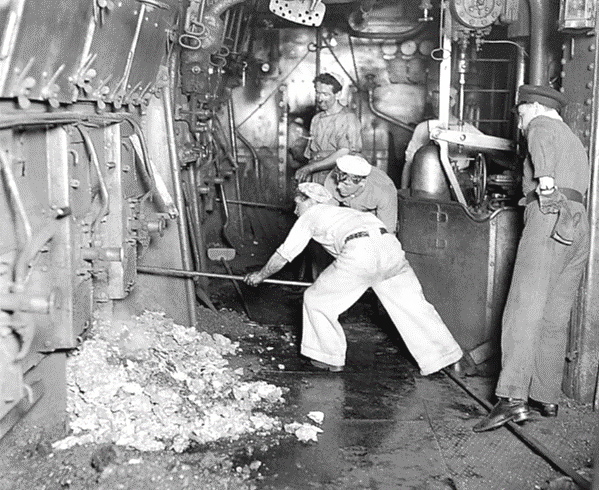

Stokers were regarded within the Navy as the lowest of the low - uncouth, uneducated and ill-disciplined men. They were, however, slightly better paid than ordinary seaman, a recognition by the Royal Navy that without stokers its ships would have been unable to move. Work conditions down in the ‘stoke-hole’ were appalling – hot, gloomy, filthy and dangerous. Stokers also had to contribute to their living costs if they wanted to eat adequately and be clothed ‘safely’ in items such as wooden clogs (leather soles melted) and fireproof woollen trousers.

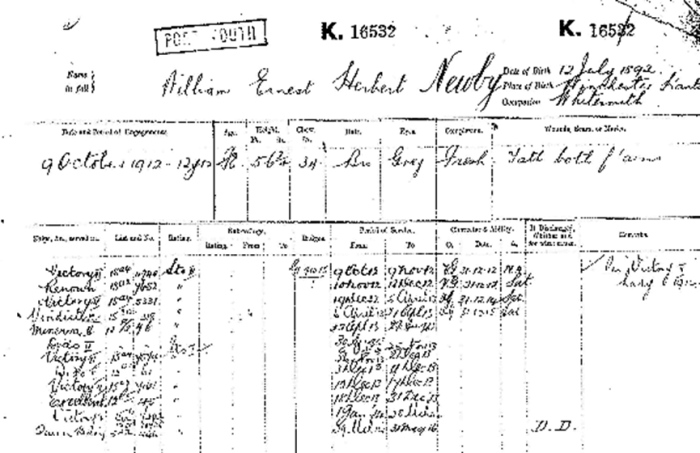

Bert Newby became K/16532, Stoker 2nd Class. His Navy records include a physical description: he was 5ft 6¾ins tall with a 34ins chest, brown hair, grey eyes and a fresh complexion. He also had tattoos on both forearms. Bert was around average height and build for the time which may have been a disadvantage when working in cramped spaces such as a ship’s boiler when it needed cleaning, one of the most unpopular tasks amongst stokers.

Bert Newby’s Royal Navy service record showing the ships on which he served

(Crown Copyright Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives)

One intriguing question is whether Bert Newby knew Charles Winter (see Charles Winter biography) before he signed up. Charles was also from the Winchester area and he enlisted in the Royal Navy as a stoker just one week after Bert. If they had not known each other before enlistment, they would certainly have soon met as both were sent on the same six-month initial training course. This was held at HMS Victory II, a shore-based training establishment near Crystal Palace, south London, for stokers and other sailors in mechanical roles.

Despite the increasing complexity of warships, a large part of the training still involved basic naval drill. For more relevant and practical experience, Bert Newby and Charles Winter then spent a month at HMS Renown, the stokers’ training ship based at Portsmouth. There they were trained in getting coal from the bunker, loading a furnace and then removing the clinker and ash. Not only was this hard, physical work but dangerous, as methane could build up in coal storage areas. Only at the end of their time on HMS Renown would Bert and Charles have been allowed to practise lighting a furnace, which on all Royal Navy ships was the responsibility of a Stoker 1st Class.

Royal Navy stokers at work – they appear to be emptying ash from a furnace.

This would have been a familiar task for Bert Newby

After completing their naval and technical training at HMS Victory II, Bert and Charles were assigned to different ships. Bert was sent to HMS Vindictive, a cruiser of a type which was being used as a tender for HMS Vernon, a torpedo training ship based at Portsmouth. After only a fortnight, on 22 April 1913, he was transferred to HMS Minerva, also based at Portsmouth and which was part of the 6th Destroyer Flotilla. He left that ship on 29 August 1913, was promoted to Stoker 1st Class the next day, which meant a little more pay, and signed off until 9 October. Throughout his career, his end of year assessments always gave his character as ‘very good’ and his ability as ‘satisfactory’.

Around this time, Bert’s mother Annie and her second husband Charles Goodenough moved from Nuns Road to 1, Ashley Terrace, off Gladstone Street, Winchester. (Ashley Terrace was a row of houses between Gladstone Street and the railway station. It was demolished in the 1960s so that Station Approach could be made a through road to Newburgh Street and Upper High Street.) It is possible that Edward and Mary Newby and their daughter Bessie moved with them as again there is no mention of Edward in Warren’s Directories. What supports this idea is that Edward appears in electoral records under that address in the 1920s.

Between October 1913 until March 1914 Stoker 1st Class Bert Newby moved between HMS Victory II and HMS Dido, a cruiser used as a depot (supply) ship. He also spent two weeks over Christmas 1913 at HMS Excellent, the gunnery training base on Whale Island near Portsmouth. A Stoker 1st Class was responsible for maintaining machinery throughout a ship, including guns, and was likely to be manning a gun during Battle Stations if not on stoking duty.

Great War Record

On 19 March 1914 Bert Newby was assigned to his final ship, HMS Queen Mary. Named after King George V’s wife, Queen Mary was a battle-cruiser which had entered service the previous year. It was under the command of Captain Cecil Prowse and was attached to Rear-Admiral Sir David Beatty’s First Battle-Cruiser Squadron, part of the Grand Fleet under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. This fleet spent the entire Great War operating in the North Sea, keeping the German High Seas Fleet in port and defending the British coast and the Atlantic trade routes. On arriving on HMS Queen Mary, Bert would have been reunited with his fellow stoker from the Winchester area, Charles Winter, who had been on the ship since 6 November 1913 and was now also a Stoker 1st Class.

The Queen Mary had 42 furnaces to be kept going if top speed was required. Consequently, almost half of the ship’s total crew complement were stokers – some 555 out of 1,266 men. A Stoker 1st Class would be spared the back-breaking task of bringing coal from the bunkers, but he would be the one to shovel the coal into the furnace. If top speed was required, this could be brutal work over the course of a four-hour watch. Nevertheless, stokers took great pride in maintaining the requested speed, especially if an enemy ship was being pursued.

Bert and Charles would have been part of the visit of the First Battleship Squadron to Russia in June 1914. They first saw action in the Great War on 28 August 1914 at the Battle of Heligoland Bight when the First Battleship Squadron was sent to assist British destroyers and submarines which had been ordered to attack German ships patrolling the German coast, but which had then come under attack themselves by superior enemy forces. The British sank several German ships without loss and hailed the battle as a great victory. However, this triumphalism masked the poor communications between the Admiralty and the Grand Fleet and between British ships and submarines which came close to them firing on each other on several occasions.

On 16 December 1914 HMS Queen Mary was part of a British force sent to intercept a German squadron on its way back from shelling the port towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby. The raid was an attempt to lure part of the British Grand Fleet out into the North Sea where the German High Seas Fleet was lying in wait. The British had been able to crack the German naval code and so knew about the raid in advance. However, they were unaware that the High Seas Fleet had left harbour and was planning an ambush. The British were only saved by the Kaiser’s reluctance to endanger his fleet and Rear-Admiral Beatty’s decision to turn his force back before attacking the superior German force.

HMS Queen Mary missed the next serious German attempt to engage part of the British Grand Fleet at the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 Jan 1915 as she was in the middle of a refit. On 24-25 April 1916, the Germans raided the East Coast again, this time Yarmouth and Lowestoft, and Rear-Admiral Beatty was sent to intercept them. However, the German force managed to slip away in the bad weather.

The background to the Battle of Jutland has been described in the chapter on William J. Mitchell (see William Mitchell's biography). HMS Queen Mary was involved in the first phase of the battle as Beatty attempted to cut off the German scouting force under Rear-Admiral Franz Hipper from its base. At the same time, Hipper was trying to lure Beatty towards the German High Seas Fleet before Beatty had been joined by the rest of the British Grand Fleet under Admiral Jellicoe.

At 3.48pm on 31 May 1916 the German ships Seydlitz and Derfflinger opened fire on HMS Queen Mary which quickly responded. After five minutes of this exchange, a rolling German salvo crashed on to the deck of the British battle-cruiser. An eyewitness reported that a dazzling flashing red flame erupted from the ship where the shells had landed. Then there was a large explosion which rent the ship into two. Clouds of black debris shot hundreds of feet into the air. The ship sank quickly with the bow plunging downwards, the propellers still slowly turning. All that was left was a dark pillar of smoke like a vast palm tree.

A pillar of smoke belches from HMS Queen Mary after she was hit by German

shells and exploded at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916. Bert Newby and

Charles Winter were among the 1,266 men who went down with the ship (Public domain)

Bert Newby and Charles Winter were among the 1,266 men who went down with HMS Queen Mary, one of three battle-cruisers among Beatty’s force to be sunk in quick succession as a result of explosion. Only 20 men survived. The wreck of the Queen Mary was discovered in 1991, resting in pieces on the floor of the North Sea. Today it is designated as a protected place under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.

Family after the Great War

In June 1917, on the first anniversary of Bert’s death, an In-Memoriam notice appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle immediately below those for William Mitchell. It is only from this entry that we know that that William Ernest Herbert Newby was known simply as Bert:

‘Newby, Bert

Missed by Ethel and friends

At 11, Greenhill Road’

In 1917, the householder at 11, Greenhill Road, Fulflood, was a Charles Meacher. According to the 1911 Census, his youngest child was Ethel Rose. She would have been about 20 in 1917 and it is tempting to think that she may have been Bert Newby’s sweetheart.

Bert’s mother Annie and her second husband Charles remained at 1, Ashley Terrace after the war. In early 1915, Bert’s brother Edward had lost his wife Mary when their daughter Bessie was only three years old. The electoral records show that Annie, Charles and Edward remained together at 1, Ashley Terrace throughout the 1920s.

Annie Goodenough died in 1933, aged 76. Her granddaughter Bessie was then 22 and had perhaps already become the family’s housekeeper. Charles Goodenough remained listed in Warren’s as the householder for 1, Ashley Terrace until 1940/1. However, the 1939 Register lists only Edward and Bessie Newby, not Charles Goodenough, as the residents at the property. Edward was a farm labourer, so had returned to his agricultural background, and Bessie a domestic servant. Charles Goodenough was found in the 1939 Register at the Public Assistance Institution (the former workhouse) on St Paul’s Hill where he was described as an ‘incapacitated patient’. Charles died in Aldershot in 1943 at the age of 84.

Edward Newby, Bert’s brother, died in 1941, aged 65. The Warren’s Directory of 1942 has Miss Newby (presumably his daughter Bessie) as the householder for 1, Ashley Terrace. Bessie never married and remained at the house until it was demolished in around 1964. She would then have been around retirement age and it may have been at that time that she moved to Southampton (there were several Newbys living in the city) where she died in 1983, aged 72.

The life of Bert’s second sister Maria has been difficult to piece together. Her husband, Alfred Meldrum, whom she married in Winchester in 1906, is believed to have come from Portsmouth and worked as a linotype operator. The couple had several children over at least a 17-year span, many of whom their Uncle Bert would have known. Maria died in 1972 in Oxford, aged 89. She was the last of Bert Newby’s three siblings to die.

Lillian Padwick, Bert’s niece, lived with her widower father Frederick for many years after the war. In the 1939 Register they were living at 11, Stoney Lane, Weeke, Winchester. Lillian was listed as ‘Mrs Ward’. A George Edward Ward had been the householder at the Red Bungalow, later 11, Stoney Lane, since 1929 so presumably he was Lillian’s husband. The Register also showed that the couple had a daughter, Sylvia, who had been born on 9 September 1930.

George Ward remained the householder of 11, Stoney Lane in the 1940s but is believed to have died in Winchester in 1950, aged 57. Lillian was recorded as being the householder for the property in 1951 but she moved shortly afterwards. Her father Frederick died in Winchester in 1960. In the 1960s and 1970s, Lillian lived at 3, Chesil Terrace, Winchester. She died in Winchester in 1982 at the age of 81.

Medals and Memorials for William Ernest Herbert Newby

William Ernest Herbert Newby is listed on

the Naval Memorial on Southsea Common in Portsmouth

William Ernest Herbert Newby was entitled to the 1914/15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. His final resting place, HMS Queen Mary off the Danish North Sea coast, is a protected war grave. He is listed (above) on the Naval Memorial on Southsea Common in Portsmouth (PR. 19) and on the memorials at St Paul’s and St Matthew’s churches, Winchester.

Additional sources

- T. Chamberlain: Life of a Stoker – thesis, University of Exeter https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/13844

- http://www.naval-history.net/xDKCas1916-05May-Jutland1.htm