Private ALFRED SCADDEN

10, Andover Road, Winchester (no longer stands)

Service number G/15680. 7th Battalion, The Buffs (East Kent Regiment) Transferred from Kent Cyclists Battalion

Missing, believed killed in action, France, 5 October 1916

Life Summary

Alfred Scadden was born in Union Street, Winchester in 1889, the son of William and Annie Scadden (the name also appears as Scaddan, Scuddan and Scuddon). His parents were not from Winchester but moved to the city a few years before Alfred’s birth. Alfred worked as an ironmonger before enlisting with the Kent Cyclists Battalion in 1915. He transferred to an infantry battalion and was killed in action, aged 27, during the later stages of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Family Background

Alfred’s father William was born on 10 April 1851 in Corfe Castle, Dorset. William’s parents, Charles (born 1814) and Fanny (1814) and his five brothers were also from Corfe Castle. In 1851 Charles Scadden was working as a labourer in a clay pit with his family living in West Street, Corfe Castle. In the 1861 Census Charles was still working in clay pits while two of his sons were clay diggers and one a brickmaker’s labourer. William, aged nine, was at school.

Alfred’s mother Annie (1858-1924) was born in Leckford, near Stockbridge. It is not known when she and William married, but they must have lived in Southampton for a time because their three elder children, Bertie (1884), Charles (1884) and Fred (1886) were all born there.

By 1886 the Scaddens had moved to Winchester and were living on the east side of Union Street at No. 36 (subsequently demolished). After Alfred’s birth in 1889 the couple went on to have two daughters – Elizabeth, born in Winchester in 1892, and Emily (1897). The 1901 Census records Alfred’s father working as a saddler and harness maker and his older brother Charles as a bottle washer. Fred and Bertie, his other brothers, had left home. At some stage, the Scadden family moved to Middle Brook Street and then, in 1908, to 10, Andover Road (the house no longer stands). By the time of the 1911 Census only 21-year-old Alfred, his parents and sister Emily were living at home. Alfred was working as an ironmonger’s assistant and Emily as a dressmaker.

Great War Record

Alfred did not join the rush to volunteer for military service when the Great War began in August 1914. Instead he waited until October 1915 before enlisting with the Kent Cyclists Battalion in Tonbridge (service number G15680). Given his choice of battalion it is likely that he was a keen cyclist.

Most of the British Army’s cyclist battalions were Territorial units that formed part of Regular infantry regiments. However, four battalions - the Huntingdonshire, Highland, Northern and Kent Cyclists - were independent and without regimental affiliation. Although it had been touted as the new form of cavalry before the war, the bicycle proved to be of limited use in trench warfare.

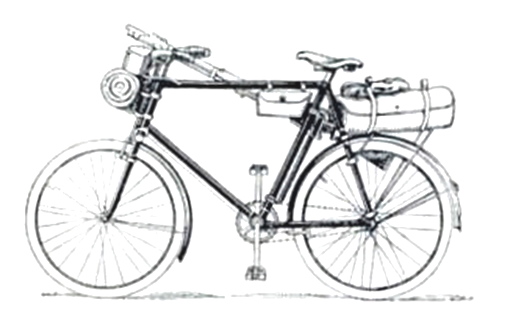

In 1915 the first units of the Army Cyclist Corps were serving primarily in reconnaissance roles and as dispatch riders. They also engaged in traffic-directing duties and helping to locate stragglers and wounded troops on the battlefield. During the war years cyclists often found themselves confronted by difficult terrain, and on numerous occasions were forced to abandon their heavy Army issue machines.

The Army bicycle was designed to enable the rider to travel as a completely self-contained one-man fighting unit. Everything from his rifle to his cape and groundsheet could be stowed away on his bike. A small kitbag carried behind the seat held rations and personal items while an emergency tool kit hung from the crossbar. ‘Cycle Artificers’ were used to maintain the bikes and members of each battalion were trained as mechanics.

The Kent Cyclists on parade – Alfred Scadden joined the battalion in October 1915

The Army drew up regulations for the use of bikes. These included such gems as:

A cyclist standing with his cycle, with rifle attached to it, will salute with the right hand, as laid down in Section 19, returning the hand to the point of the saddle on the completion of the salute. When at ease, a cyclist, whether mounted or leading his bicycle, will salute by coming to attention, and turning his head to the officer he salutes. A party of cyclists on the march will salute on the command Eyes Right, which will be followed by Eyes Front, from the officer or NCO in charge.

The rate of marching, excluding halts, will generally vary from 8 to 10 miles per hour, according to the weather, the nature of the country, and the state of the roads. A column of battalion size should not be expected to cover more than 50 miles in a day under favourable conditions.

A Great War Army bicycle of the type that

Arthur Scadden would have used

However, Alfred’s time with the Kent Cyclists was brief. On 2 December 1915, the 1/1st Kent Cyclist Battalion moved to Chisledon Camp, Swindon, Wiltshire, to be reorganised as an infantry battalion. It is believed that this was when Alfred transferred to the East Kent Regiment – known as The Buffs - and assigned to the 7th (Service) Battalion. The 7th Buffs had been raised at Canterbury, Kent, in September 1914 as part of Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener’s expansion of the British Army. The battalion came under the command of 55th Brigade in the 18th (Eastern) Division.

After a period of training, Alfred joined the 7th Buffs on the Western Front in time for the start of the Somme Offensive on 1 July 1916. Although the British suffered some 58,000 casualties on that disastrous first day of battle, the 18th Division, including the 7th Buffs, successfully achieved all its objectives. Attacking German positions near the village of Montauban at the southern end of a 13-mile front, 18th Division captured the formidable defensive systems known as The Loop, Pommiers Trench and Pommiers Redoubt.

One interesting footnote concerns the battalion attacking to the right of the 7th Buffs on 1 July, the 8th East Surreys. When the order came to go over the top at 7am Captain W.P. Nevill led his four platoons into battle, each platoon kicking a football towards the German front line for the honour of scoring the first ‘goal’ Captain Nevill was killed but his platoons continued the advance. Two of the footballs were retrieved and one is now in the National Army Museum.

The 7th Buffs were in action again on 13-14 July when 18th Division was given the task of capturing Trones Wood, north of Montauban. Alfred’s battalion led the attack, bombing their way up Maltzhorn Trench on the edge of the wood. After fierce German resistance and heavy British casualties, 18th Division eventually took Trones Wood in the early hours of 14 July.

Alfred and his battalion were out of the front-line during August but returned at the end of the following month for the Battle of Thiepval (26-28 September) and the Battle of the Ancre Heights (1-18 October). Among the objectives in the latter battle was Schwaben Redoubt which had been briefly captured on 1 July and then retaken by the Germans. The ferocious fighting around the Redoubt is vividly described by military historian Barry Cuttell:

This close-quarter work with bomb and bayonet was one of the most dangerous aspects of infantry work, during which all opposing sensations were experienced – fear-excitement, indecision-confidence, despondency-elation, despair-hope, what is today called a surge of adrenaline. Gains by both sides were made and lost, and at the end of the day the line had changed little. Losses were very heavy on both sides.

Alfred Scadden is believed to have been killed, aged 27, in an attack on the Schwaben Redoubt on 5 October 1916. His body was never found. The British finally captured the Redoubt on 14 October.

Family after the Great War

Alfred’s father William continued to live at 10, Andover Road immediately after the war. However, his name is not listed in Warren’s Directory after 1920 which suggests that he may have died around that date. Annie Scadden, Alfred’s mother, died in Winchester in 1924. Warren’s lists a Miss Scadden at 10, Andover Road from 1920 to 1926 and she is almost certainly one of Alfred’s sisters.

Medals and Memorials for Arthur Scadden

Inscription on Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France

Private Alfred Scadden was entitled to the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. His name appears (misspelt as Scuddan A) on the Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France (Pier & Face 5D) and also on the memorials at St Matthew’s and St Paul’s churches, Winchester.

Additional sources

- Cuttell, Barry. 148 Days on the Somme (Peterborough, GMS Enterprises, 2000)