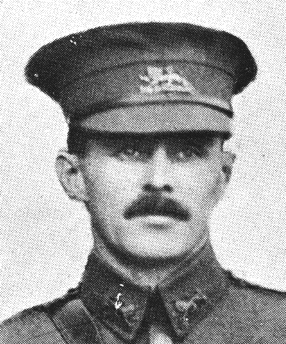

Major JOHN HENRY MORRAH

25, Cranworth Road, Winchester

1st Battalion, The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment

Killed in action, France, 18 October 1914

Life Summary

Major John Henry Morrah

John Henry Morrah was a career soldier who served throughout the British Empire for nearly 20 years before the Great War. He came from a distinguished upper middle-class family. His father, also an Army officer, later served as Mayor of Winchester while his elder brother was a President of the Oxford Union and later found success as a poet and novelist. John, known as Micky to his Army colleagues, was decorated for gallantry during the Boer War. In the Great War he was one of the ‘Old Contemptibles’ who fought on the Western Front in the summer and autumn of 1914. He was killed by a German sniper in Flanders in October 1914.

Family Background

John Morrah was born in Derby on 20 July 1875. His parents were living at 93, Friar Gate at the time and it is likely that his mother, Mary, gave birth to John in the house. James Morrah, John’s father, was a Captain in the 60th Rifles (later the King’s Royal Rifle Corps) based in Derby. James had been born in 1832 in Chelsea, west London, where his father, also called James, was a surgeon. James Morrah Snr’s brother (John’s great uncle) also practised medicine and had been assistant surgeon in the 1st Battalion, the 4th Regiment of Foot at the Battle of Waterloo. The 4th Regiment of Foot later became the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment in which John Morrah served. James Morrah Snr’s wife, Elizabeth (née Pasmore), had lived in Clifton, Bristol, where the couple married before moving to London.

James Morrah Jnr went to Westminster School, where he was a Queen’s Scholar, before going on to Oxford. He joined the Army in 1854 and between September and December served briefly with the 3rd West India Regiment and the Cape Mounted Rifles. In 1855 he was commissioned into the 60th Rifles as a Lieutenant and served at that rank for five years. In 1860 he became Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion which took part in the capture of the Taku Forts and the surrender of Peking that year. He was awarded the China War Medal with two clasps in recognition of his service during the campaign.

James was Adjutant of the 7th Battalion at Winchester from 1863 to 1870 when he was appointed Staff Officer of Pensioners, serving in King’s Lynn, Canterbury and Woolwich. He retired with the honorary rank of Colonel on 20 March 1887. James Morrah married twice. He had four daughters by his first wife, Emma (née Boulton), although only two, Frances and Emily, survived into adulthood. Emma died in Winchester on 13 May 1867, aged 37, possibly from complications while giving birth to Emily.

James married for a second time on 24 August 1869 in Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey. His new wife, Mary Lister, had been born in Norton, Derbyshire on 24 June 1844 and was the daughter of civil engineer John Lister and his wife Elizabeth. Mary was living in Kingston and James in Winchester at the time of their marriage.

The couple quickly started a family. A son, Herbert, was born in Winchester in 1870 followed by William in King’s Lynn the following year. In late 1872 Mary Morrah gave birth to a daughter, Gertrude, in King’s Lynn and then a third son, Edward, also in King’s Lynn, in 1874. After John’s birth in Derby in 1875 the Morrahs had a sixth child, Mary, who was born in Derby in 1876.

93, Friar Gate, Derby - the house where John Morrah

is thought to have been born on 20 July 1875

In 1888, following James’s retirement from the Army, the Morrahs moved to Westgate House, 81, High Street, Winchester. The 1891 Census showed four daughters and four servants residing at the property in addition to James and Mary. The daughters included Frances, then 27, and Emily, 23, James’s children by his first wife Emma. The census also revealed that the Morrahs’ sons, John and Edward, were boarders at Eastbourne College, Sussex.

John’s father eschewed a quiet retirement and threw himself into local politics. In 1889 he was elected to Winchester Town Council as a Conservative member for St Thomas ward. Two years later he became Mayor of Winchester, a significant achievement for a man with little political experience. James Morrah served on no fewer than nine council committees in addition to his official duties as mayor.

James continued as a councillor until his death on 14 May 1893, aged 61. Among his many other roles he was chairman of the Executive Committee of the Conservative Association, a member of the Primrose League (an organisation founded in 1883 to spread Conservative principles throughout Britain), treasurer of the Elementary Schools Council and president of the Winchester Volunteer Fire Brigade. Clearly hugely respected, the Hampshire Chronicle’s report of his death (Death and Funeral of Col. J.A. Morrah, 20 May 1893, p.5) noted of his time as Mayor: ‘How worthily he fulfilled the duties of the office during the year 1890-91 is still fresh in the memories of the citizens.’ James’s funeral was held at St Thomas’s Church with his coffin carried by sergeants of the Rifles. In his will he left £11,871 9s 3d (equivalent to more than £1.5 million in 2019) to his wife Mary and son Herbert.

Mary Morrah continued to live at Westgate House until 1895 when she moved to Glasnevin, a large property in Barnes Close, St Cross, Winchester. The house, No. 3 on the north side of the road, was later renamed Trevean. Mary remained there until 1905 when she moved a short distance to The Willows, another imposing house, on the western side of St Cross road. The property no longer stands and today the site is occupied by modern homes. In 1911 Mary moved once more, this time to West Dene at 25, Cranworth Road, thus beginning the Morrah family’s association with Fulflood and Weeke.

Early Military Career

In 1893, the year that his father died, John Morrah won a Queen’s Cadetship to Sandhurst. He was helped in this by the interest of several influential military figures, including the Duke of Connaught, son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who later became a Field Marshal in the British Army. Such prominent connections show that John and his family moved within the very highest echelons of British society.

John left Sandhurst in 1895, was commissioned into the 1st Battalion, The King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment in March the following year and appointed Lieutenant in November 1897. In the 1901 Census he was living at Tournay Barracks, part of the Aldershot Garrison.

Although the 1st King’s Own never fought in South Africa during the Second Boer War John Morrah did. In October 1901 he was sent out to command the regiment’s 27th Company of Mounted Infantry and took part in operations in the Transvaal, Orange Free State and Cape Colony before being severely wounded in an engagement with Boer forces at Vredefort in the Orange River Colony on 17 December. Invalided home in February 1902, he spent several months recuperating before rejoining his regiment. John was awarded the Queen’s Medal with four clasps for his services during the campaign.

On 19 November 1903 John, by then based in Malta, married Maud Macgregor at St George’s Church, Hanover Square, London. Four years older than her husband, Maud had been born in October 1871 in Bombay (modern Mumbai), India. Her father, Cortlandt Macgregor (previously Macgregor-Skinner), was born in Bombay in 1841 and later became a Major in the Royal Engineers. After retiring from the Army, he held the post of Registrar at the Royal College of Science, which was later absorbed into Imperial College. He died in 1893 in Germany. Maud’s mother, Sophie (née De Koehler and known as Zosha), was born in Warsaw, Poland, in February 1848. In the 1901 Census, Maud was living with her mother at 15, Carlisle Place, Hanover Square.

John Morrah (pictured seating second from the right, second row up)

with his fellow battalion officers in around 1910

Maud’s elder sister, Alice, had married John’s brother Herbert in 1895 so it is likely that John and Maud had known each other for some time. The newlyweds initially lived in London where a daughter, Marjorie, was born in 1904. Maud gave birth to a son, Michael, in 1907 in Lancaster where, presumably, her husband was stationed at the time.

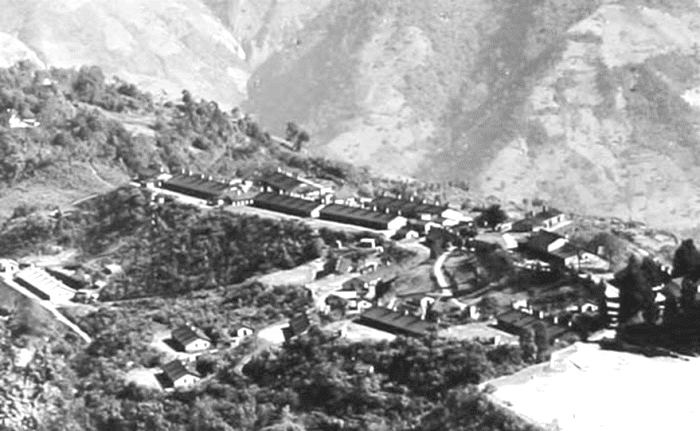

It has been difficult to precisely track the progress of John Morrah’s military career, but it is believed that he also served overseas in Hong Kong, Singapore and Burma (modern Myanmar). Between 1908 and 1910 he held a special staff appointment as Adjutant of the Madras (modern Chennai) Volunteer Guards. The United Grand Lodge of Freemason Membership Registers (Colonial and Foreign section) reveal that John was initiated into the Freemasons in October 1908 when he was living in Lebong, near Darjeeling in northern India. It is not known whether John’s family accompanied him to India. However, the 1911 Census, compiled after John had returned to England, showed Maud and the two children living at 29, Cardigan Road, Richmond, west London. John, meanwhile, was recorded as residing in Winchester at The Willows, together with his mother and sister Mary Grace. It is likely that John was merely visiting at the time of the census because by 1912, the year he was promoted to Major, his wife gave birth to a second daughter, Joyce, in Dover where his battalion was stationed at the time.

The British Army base at Lebong, near Darjeeling, northern India, where John

Morrah was stationed in 1908.It was while here that he was initiated into the Freemasons

Siblings

What, meanwhile, of John’s siblings? The eldest brother, Herbert Morrah, is perhaps the most interesting. Educated privately at Highgate School, London, he later attended St John’s College, Oxford, where he was President of the Union. Herbert made several influential friends at Oxford, including F.E. Smith, later a leading Conservative politician, who would rescue Herbert’s reputation from potential scandal in the 1920s.

On 13 June 1895 Herbert married Alice Elise Macgregor in Kensington, West London, and the couple’s first child, Dermot, was born in Ryde, Isle of Wight, on 26 April 1896. By this time Herbert had already embarked on a literary career. This had begun in 1894 with a volume of verse, ‘In College Fields’, followed by three novels, ‘A Serious Comedy’ (1896), ‘The Faithful City’ (1897) and ‘The Optimist’ (1898). In February 1898 Alice gave birth to a daughter, Stella Margaret, in Ryde followed by a second girl, Kathleen Cecilia, in London in November 1901. The census in April of that year showed the family living at 51, Ravenscourt, Notting Hill, west London, with Herbert working as an author and editor.

By 1911, Herbert, Alice and their children had moved to 14, Addison Gardens, Kensington, west London. That year saw the publication of Herbert’s book Highways and Hedges in which he describes the charm of English country life. His words are accompanied by romantic colour landscape plates by the artist Berenger Benger. By contrast, the life of Edward Morrah was blighted by tragedy. After leaving Eastbourne College he served an apprenticeship as an electrical engineer and was inducted into the Institute of Electrical Engineers in 1899. However, on 15 January 1900 Edward was admitted as a patient to Menston Lunatic Asylum, near Leeds, Yorkshire, where he died three months later, on 25 April at the age of 26.

John Morrah’s other brother, William, was musically gifted and he worked for a time as a ‘vocalist’. In April 1903, William married French-born Marguerite Longhurst, the daughter of a journalist. By 1911 the couple were living in Friern Barnet, Middlesex, with their daughter, Marie. The census of that year recorded William’s profession as a ‘traveller in motorists’.

Gertrude Morrah, John’s elder sister, qualified as a midwife in 1902 and by 1904 she was working at Guy’s Hospital, London. On 26 January 1909 Gertrude married Leonard Latham Wickham, the son of Winchester clergyman Henry Wickham, in Vepery, Madras, India. Leonard worked as an executive engineer for the Madras Public Works Department before retiring in 1914. At this point the couple returned to England and Gertrude went back to work at Guy’s Hospital.

Great War Record

The 1st King’s Own (Royal Lancaster) Regiment were still based in Dover serving with 12th Brigade, part of 4th Division, when the Great War broke out in August 1914. Fears of a German invasion meant the Division was held back from the original British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sent to the Continent, but when it became clear that the Germans did not intend to cross the Channel this decision was reversed and the 4th Division embarked for France aboard the SS Saturnia, landing at Boulogne on 23 August. The same day the BEF fought its first major engagement of the war at the Battle of Mons.

25, Cranworth Road, Winchester – home to John Morrah’s mother and,

following her death in 1920, his sister Mary Grace

Within days, John Morrah’s battalion was involved in fierce fighting at the Battle of Le Cateau. Early on 26 August, after an all-night march to cover the retreat of the main body of the BEF from Mons, the King’s Own were resting at Haucourt, near Le Cateau, when they suddenly came under murderous German artillery and machine-gun fire. The battalion suffered more than 430 casualties in a single two-minute burst of machine-gun fire which nearly destroyed it as a fighting unit. Among the 64 men killed was the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Dykes.

Captain (later Colonel) Lionel Cowper was among those who fought with the King’s Own at Le Cateau and he later described his devastating first experience of modern industrial warfare. The men, he wrote, were waiting to have their breakfasts when ‘a tremendous burst of machine-gun fire opened on them, killing Colonel Dykes almost immediately [his dying words were ‘Goodbye, boys’]. Then the German artillery began to shell the battalion’s positions:

At first their fire was short, but they soon found the range and the shells started to burst about thirty to fifty yards in front of the leading company. The first burst of fire did not touch the transport and some of the drivers tried to turn their horses round and get them to cover, but the machine guns then appeared to lengthen the range and bullets began to drop amongst them. Then came the shells, and chaos ensued. The first shell hit the cooker; the mess cart was immobilised with the horses dead between the shafts; the remaining horses bolted and some of the vehicles got locked together; others, both horse and vehicles, galloped off in all directions; the jackets of the machine guns were reported to have been holed and therefore useless. The small dog, for which the men had made a coat out of a Union Jack, was killed as he stood next to the driver of a wagon. One by one company commanders tried to get their men to cover, but ‘C’ Company was almost entirely wiped out.

Fighting raged for most of the day with the King’s Own continuing to take casualties. Following the death of Colonel Dykes and with the second in command temporarily missing, John Morrah took over as CO. Captain Cowper’s account continues:

[W]hen it was later possible to discover the losses in the battalion they were found to be five officers killed, six wounded, of whom two were taken prisoner, and one missing; no less than 431 other ranks were killed, wounded and missing, a total which, even in the bloody battles of Ypres and the Somme, was never reached again in a single day by the 1st Battalion. This introduction to war was a rude shock to the majority who had never previously a shot fired in anger. Even those who had served in South Africa were unprepared for anything of the sort, and Grover declared that Spion Kop was ‘child’s play’ in comparison.

Over the following days the King’s Own, together with the rest of the BEF, were pushed back towards Paris by the advancing German armies. Although no longer CO, John Morrah is believed to have been second in command and his military experience would have proved invaluable in maintaining his men’s morale during this period of exhausting forced marches. The King’s Own then featured in the Allied counterattack at the Battle of the Marne (5-9 September) which first halted and then pushed back the Germans. John was appointed temporary CO on 9 September and he led his battalion during the Battle of the Aisne (12-15 September). At the Aisne, the Germans began to dig in along the high ground of the Chemin des Dames ridge, signalling the start of trench warfare on the Western Front.

After nearly a month on the Aisne, the King’s Own were sent north to Flanders with the rest of the 4th Division, arriving at Hazebrouck on 12 October. Nine days earlier, John Morrah’s spell in charge of the battalion had come to an end with the appointment of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Creagh-Osborne as CO. This was probably more to do with John’s relative inexperience rather than a reflection of his performance as acting CO – after all, he had been a Major for less than two years.

On 13 October, the King’s Own joined an attack by the British III Corps on the town of Meteren during the opening phase of the Battle of Armentieres (13 October-2 November). The battalion advanced across flat country through a thick early morning fog which unfortunately lifted as the troops approached Meteren where the Germans occupied houses with an excellent field of fire. Captain Cowper was again in the thick of the action:

As soon as the battalion emerged from the lane it came under machine-gun and rifle fire, but there was no hesitation and the men continued to advance in perfect order by the orthodox method of the time, in short rushes. The plan was for the machine guns to cover the advance by engaging with fire the enemy on the southern outskirts of the village, but no sooner did [Lieutenant Anthony] Morris emerge from the farm enclosures than he was seen from the church tower. He took up a position behind a scanty hedge, where he and his team were later found in a tidy row of eight, all dead and their gun out of action.

Visibility was so poor that the artillery was never able to support the advance, and with the battalion machine guns out of commission there was nothing to hinder the enemy fire. So heavy did it become that all four companies were driven to find cover as best they could in the wet ditches and hedgerows on their right and in their rear … Sergeant E. Howard crawled out into the open to find out why twelve men who were lying there did not fire, though he shouted at them to do so. He found them all dead. The Lancashire Fusiliers were ordered to fill the gap on the right of the King’s Own, but by nightfall they had not arrived and the Regiment had to continue to protect its own flanks.

After dark, the wounded were collected up in the farmhouse, and the Lancashire Fusiliers not only came up on the right of the King’s Own but pushed on into Meteren, which they found deserted. Most of the next day was spent in clearing the battlefield … The men were horrified to see how little of Meteren was still standing. Whole families were homeless, and the small children who begged for bully beef did not ask in vain.

The attack on Meteren cost the King’s Own another 36 men killed, 34 wounded and 15 missing. Seven more died of wounds over the next two days.

A newspaper report of Major John Morrah’s death in 1914

Major John Morrah's Queen’s Medal

with four clasps which he received

for his bravery during the Second Boer War

in 1901

On 18 October, Major John Morrah was shot dead by a German sniper near Armentieres as he attempted to signal to officers of a neighbouring regiment. Colleagues reported that he died instantly. John fought on the Western Front for less than two months, but in that time he impressed with his bravery, coolness under fire and inspirational leadership. He was posthumously mentioned in BEF Commander-in-Chief Sir John French’s Despatch of 14 January 1915. News of his death soon reached Winchester and on 7 November 1914 the Hampshire Chronicle published the following obituary (The Casualty List, p. 10):

Major John Henry Morrah, the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, who was killed in action on October 18th, aged 39, was the youngest son of the late Col. James Arthur Morrah, formerly of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and was educated at Eastbourne College and Sandhurst. He received his commission in March 1896 and was appointed Lieutenant in November 1897, Captain in May 1901 and Major in December 1912. He served in the South African campaign, in which he was severely wounded, receiving the Queen’s medal with four clasps, and was afterwards continuously employed on active service in India and other parts of the Empire viz, at Malta, Hong Kong, Singapore, Calcutta, Burma, Darjeeling, Madras (as Adjutant of the Madras Volunteer Guards), South Africa etc. The late Major Morrah was dangerously wounded near Vredefort on December 17th 1901. He married, in 1903, Maud Florence, younger daughter of the late Major Cortlandt Macgregor RE, and leaves a widow and three children, for whom, together with his mother and two sisters, who reside at Winchester, much sympathy will be felt.

A brother officer wrote of him: ‘He really was a gallant officer, how gallant only we who saw him from day to day can tell, going about among the men with conspicuous coolness when danger was greatest and bullets were thickest – an example of sterling bravery. Today the Regiment that has done so much, and is still going to do more, is the poorer by a gallant officer, an English gentleman, and a sincere and keen soldier.’

Another correspondent writes: Major John Henry Morrah was the youngest son of the late Colonel James Arthur Morrah, whose connection with the city of Winchester dated from the year 1854, when he received his first commission in the 60th Rifles, and was continued in various ways until his death in 1893, including the Mayoralty, which he held in the year 1891.

The late Major Morrah, who received the honour of a Queen’s Cadetship at Sandhurst, through the kindly interest of the late General Montgomery and other Riflemen, including H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught, received his earlier education at Eastbourne College, of which he remained always a loyal and attached member. His choice of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment was due to the association therewith of his great uncle, William Morrah, whose record was one of considerable distinction and included the Battle of Waterloo.

The late Major Morrah was gazetted to his Regiment in 1896. His promotion was rapid – in 1901 he secured his company and in 1912 his majority. He served in a number of different stations, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Burma, as well as in England, and on the staff he held a special appointment from 1908 to 1910 as Adjutant of Indian Volunteers at Madras. In the South African War he took part in the operations in the Transvaal, the Orange River Colony, and Cape Colony and during the campaign he was very severely wounded. He held the Queen’s medal with four clasps.

In the present campaign the deceased officer had taken part in many important engagements and during the whole of the time up to the middle of October his letters had been full of interesting details, written with the spirit for which he was famous in his Regiment and amongst a large circle of friends. He fell the victim of a German sniping bullet, and his death was mercifully instantaneous. It is understood that at the moment of the fatal shot he was standing up to signal to the Seaforth Highlanders across the river, and that the operations, which were shared by Major Lysons and Captain Lendon of the same Regiment, took place in the neighbourhood of Le Touquet. These two officers subsequently fell and the three were buried side by side.

Of his brilliantly sunny temperament, as well as of his fine soldierly gifts and qualities, ‘Micky’ Morrah, as he was often familiarly known, leaves an ineffaceable impression, and many accounts received from the front since his lamented death speak in the most glowing terms of his admirable courage, cheerfulness and unselfishness, whatever the circumstances.

Family after the Great War

Maud Morrah and her three children were living at 129, Hamlet Gardens, Ravenscroft Park, west London, when John died. However, when probate was granted, on 29 April 1915, her address was given as 77, The Esplanade, Dover. John left his wife an estate valued at £1,373 15s 3d. Army records show that Maud also received £29 13s in respect of lost kit in May 1915, a further payment of £21 in July 1915 and a £60 war gratuity in September 1919. Maud never remarried. She later emigrated to Southern Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) to be with her daughter Marjorie who had moved there in 1946 with her husband Linzee Otho Wooldridge. Maud died in Salisbury (now Harare) on 12 April 1959, aged 87. Marjorie died in 1982, aged 78.

Michael Morrah, John’s son, trained as an accountant. He married Catherine Day in Bromley, south London, in 1935 and spent much of his working life overseas, particularly in the Caribbean and the United States. The couple had at least one child, a daughter called Anne, born in 1937. Michael returned to England and died in Ploughley, Oxfordshire, in December 1977, aged 71.

John’s youngest child, Joyce, was recorded working as a shorthand typist in 1939 and living with her elderly mother at 156, Sussex Gardens, Paddington, London. In 1946, the same year that her sister Marjorie moved to Rhodesia, Joyce married Charles Stumbles, the Civil Commissioner for Southern Rhodesia in Durban, South Africa. Her place and date of death are not known.

Mary Morrah, John’s mother, continued to live at 25, Cranworth Road, Winchester, until her death in 1920, aged 76. Her daughter, Mary Grace, had presumably been living with her for some years because her name then appears as the householder of the property in Warren’s Directories until 1929. In 1931 Mary was recorded as living with her sister Gertrude and husband Leonard Wickham at 10, Compton Road, St Cross, Winchester. Gertrude is believed to have died in Winchester in 1932 and the same year Mary Grace moved to 2, St James’s Villas, Winchester, where she remained until her death, aged 76, on 11 December 1942. Interestingly, Mary Grace’s stepsister, Emily, who it is believed served as a nurse at Guy’s Hospital while Gertrude Morrah worked there as a midwife, was living with her when she died.

William Morrah, John’s brother, does not appear to have fought in the Great War. Instead, he continued to live in London with his family; by 1936 he and wife Margueritte were in Harrow and in 1939 in Wembley with William recorded working as a ‘superintendent at Selfridges’. He is thought to have died in St Albans, Hertfordshire, in March 1953, aged 81.

Herbert Morrah, John’s artistic eldest brother, enlisted in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve in 1914 and worked for the Admiralty in Room 40, a top-secret intelligence department. The predecessor of the code-breaking centre at Bletchley Park in the Second World War, Room 40 provided vital intelligence to the British military and their allies between 1914-18. Its main task was to intercept and decrypt German wireless and telegraph messages, particularly those relating to German shipping and U-boats. After the war Herbert returned to civilian life, but in 1927 found himself at the centre of a scandal when he was prosecuted for what the newspapers of the day somewhat coyly described as ‘an offence in a West End theatre’. Fortunately, he was able to call upon his old university friend F.E. Smith - by this time Lord Birkenhead and Lord Chancellor of England – as a character witness and his evidence led to Herbert’s acquittal. Herbert’s wife Alice died in Bristol in September 1930, aged 61. Herbert himself died in hospital in Sutton, Surrey, on 20 March 1939, aged 68. His son Dermot, by this time a successful journalist with the Daily Mail, had also served in the Great War as a Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. Dermot’s grandson is the journalist Tom Utley, a long-time columnist on the Daily Mail.

Medals and Memorials for John Henry Morrah

Le Touquet Railway Crossing Cemetery, Comines-Warneton,

Hainaut, Belgium

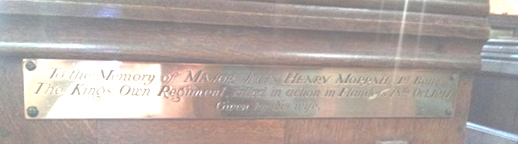

A pew plaque commemorating John Morrah in St Mary’s Priory Church, Lancaster.

Major John Henry Morrah was entitled to the 1914 (Mons) Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. He is buried at Le Touquet Railway Crossing Cemetery (grave right), Comines-Warneton, Hainaut, Belgium, (GR. A. 6). His name appears on the memorials at St Paul’s, St Matthew’s and St Thomas’s churches, Winchester, and the Eastbourne College and Royal Lancaster Regiment memorials. There is also a pew plaque (above) commemorating John Morrah in St Mary’s Priory Church, Lancaster.

Additional sources

- Colonel Lionel Cowper: The King’s Own, The Story of a Royal Regiment, Volume III, 1914-1950. (Oxford, 1939)

- https://www.eastbourne-college.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/esorg-roll-of-honour-2018-08-15.pdf

- https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2017/10/05/room-40-at-the-admiralty

- https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/137935-kings-own-royal-lancaster-regiment-war-diaries/

- http://www.kingsownmuseum.com/fww-centenary1914augactions.htm