Brigadier-General RONALD CAMPBELL MACLACHLAN

Langhouse, Chilbolton Avenue, Weeke (no longer stands)

General Staff. Commander, 112th Infantry Brigade Previously Commanding Officer, 8th Battalion, The Rifle Brigade

Killed in action, Belgium, 11 August 1917

Life Summary

General Ronald Campbell Maclachlan

Brigadier-General Ronald Campbell Maclachlan is the highest-ranking name on the Fulflood and Weeke memorials. From a wealthy, high-achieving Scots background, he moved to Weeke with his wife and family a few months before the outbreak of war in 1914 and consequently his Winchester connections did not run deep. Ronald was one of four brothers who served in the Army. He fought in the Boer War and served in other theatres in the British Empire. Later he earned a reputation as an inspirational leader and trainer of men. In the Great War he commanded a new battalion of the Rifle Brigade on the Western Front before winning promotion to Brigadier-General. He appeared destined for even higher command before a German sniper’s bullet cut short his life in 1917 at the Third Battle of Ypres.

Family Background

Ronald Maclachlan was born on 24 July 1872 in Newton Valence, a small village south of Alton. He was the seventh of nine children born to the Reverend Archibald Neil Campbell Maclachlan, patron and vicar of the parish, and his wife Mary. The family boasted a strong military tradition: Ronald’s paternal grandfather, also called Archibald, had been a career soldier with the 69th Regiment of Foot (later the Welch Regiment) and reached the rank of Lieutenant-General. Like his wife Jane (née Campbell), Archibald had been born in Argyllshire, the heartland of the Maclachlan clan which had links to the Campbells. Jane’s brother, Neil Campbell, was also a soldier and saw action in the Napoleonic Wars. He was appointed to accompany Napoleon into exile on Elba in 1814 and then fought at Waterloo the following year.

Archibald and Jane Maclachlan married in 1811. By the 1841 Census they were living in Southampton, then a fashionable spa town and retirement location for the wealthy. Their house, a handsome, newly-built terraced property in Rockstone Place, off The Avenue, was later numbered 8 and remained in the family for the next 60 years. The census showed that several relatives were living in the house with them.

The Maclachlans had three children. Their elder son, James, served in the Army but died of yellow fever in Jamaica in the early 1840s while their daughter, also called Jane, died in India in 1838, possibly in childbirth. The couple’s surviving son, Archibald Neil (Ronald’s father), went on to study at Exeter College, Oxford. After graduating, he was ordained into the Church of England and in 1846 became curate at New Alresford, near Winchester, and shortly afterwards at Old Alresford. In 1850, aged 30, he became chaplain of St Cross Hospital in Winchester.

By the 1851 Census Archibald and Jane Maclachlan had moved from Southampton to 19, Albion Street, Paddington, west London. However, the couple must have returned to Southampton because Lieutenant-General Maclachlan’s death in 1854 was recorded there. Jane then continued to live at 8, Rockstone Place until her own death in 1878.

In 1855 the Rev. Archibald Neil Maclachlan married Mary Elizabeth Sidebotham in Whittington, near Worcester. Mary, then aged about 22, had been born in Worcester and was the daughter of Charles Sidebotham, a barrister and police magistrate, and his wife, also called Mary. Five years passed before the couple’s first child, Mary Abigail, was born in Worcester on 22 September 1860. Following her birth, the family moved to Newton Valence where Archibald had bought the patronage of the living from the incumbent vicar of St Mary’s Church which meant he was able to nominate himself as the new vicar.

The Maclachlan family went to live in The Vicarage, a large 19-room house, where they employed three live-in servants and a groom-gardener. More children quickly followed: Eveleen on 12 February 1862, Archibald in about 1864, Neil (1865), Lachlan (1868) and Elsie Jean, who was born on 12 November 1869. Interestingly, the 1871 Census recorded the Maclachlans living not in Newton Valence, but with the Rev. Maclachlan’s mother at 8, Rockstone Place in Southampton. This was probably because Newton Valence had been struck by an outbreak of diphtheria at the time – one family alone lost no fewer than six children.

The diphtheria danger had clearly passed by 1872 because on 24 July that year Ronald Maclachlan was born in the village. Mary gave birth to two more sons in Newton Valence - Alexander Fraser, on 23 July 1875 and Ivor Patrick in 1878. Tragically, Ivor was born mentally handicapped and he spent much of his life being cared for by private nurses. (A later census described him as an ‘imbecile from birth’, although the term ‘imbecile’ in the 19th Century did not have the same negative connotations that it does today and meant a person with development issues.)

By the 1881 Census, three of the Maclachlan boys were at boarding school – Archibald and Neil at Eton and 12-year-old Lachlan at Cheam Preparatory School, situated between Basingstoke and Newbury. Shortly afterwards, Ronald also started at Cheam where he remained until 1886 when he joined his brother Lachlan at Eton. A fine sportsman, Lachlan played for the Eton Cricket XI and excelled at the college’s traditional games of Wall and Fives. From Eton he went straight to Sandhurst before joining the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) in 1888, the same year that Neil Maclachlan was commissioned into the 1st Battalion, The Seaforth Highlanders.

On 25 March 1891, the Rev Archibald Maclachlan died, aged 61. The subsequent disposal of his financial assets gives a glimpse of the family’s wealth. In June 1891 Great Western Railway shares owned by the Rev. Maclachlan and valued at £48,329 0s 9d were transferred to his widow. Today these would be worth nearly £6 million, and this probably represented just a fraction of the vicar’s total estate. An interesting footnote is that following her husband’s death Mary Maclachlan was passed the right to nominate the new vicar of Newton Valence. She chose her eldest son, Archibald, who took up the post in early January 1895. Archibald had studied theology at Oxford and after completing his training for the priesthood had been ordained by the Bishop of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral in December 1893.

Early Military Career

Meanwhile, Ronald Maclachlan was following in the military footsteps of his other older brothers. After leaving Eton in 1892 he went to Sandhurst before being commissioned into the Rifle Brigade on 8 July 1893 as a 2nd Lieutenant. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 27 November 1895 and then posted to Rawalpindi in northern India (modern Pakistan) with the 3rd Battalion. While an excellent career move, for Ronald the posting would have been tinged with sadness because on 10 March 1895 his brother Lachlan, serving with 1st KRRC, had been killed in a polo accident in Rawalpindi. Lachlan was aged just 27 and had been stationed on India’s North West Frontier for the previous four years. There is a lancet window in Newton Valence church in his memory.

In another part of the British Empire, Captain Neil Maclachlan was distinguishing himself with the 1st Seaforth Highlanders. In 1897 he served in the international military occupation of Crete, aimed at helping the Greek occupants who had rebelled against Ottoman Turk rule. The following year he joined up with British forces in the Sudan under General Horatio Kitchener who were fighting to recover the region from the Mahdists/Dervishes and to avenge the death of General Charles Gordon at Khartoum. Neil was seriously wounded at the Battle of Atbara in April 1898 but recovered to take part in the decisive British victory at Omdurman in September for which he was mentioned in dispatches. He also received the British Medal and the Khedive’s Medal with two clasps. After a spell in Cairo, Neil was promoted to Major in 1903 and posted to India with his battalion.

In September 1899 Ronald Maclachlan was sent to South Africa with 2nd Rifle Brigade to fight in the Second Boer War (1899-1902). He was joined there by his young brother Alexander who had been commissioned into 3rd KRRC earlier that year, making him the fourth Maclachlan brother to pursue a military career. Alexander had previously been to Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, before enrolling at Sandhurst for his officer training.

While in South Africa, Ronald and Alexander were fighting quite close to each other at times, although it is not known whether they met up. Ronald arrived at Durban on 26 October 1899 to assist in the defence of the British garrison at Ladysmith in Natal. The subsequent siege by a large Boer force lasted from 2 November to 28 February 1900 when the garrison was finally relieved, after several failed attempts, by General Redvers Henry Buller (with one Lieutenant Winston Churchill among the first group of soldiers to arrive).

The intervening three months saw several fierce engagements, including the Battle of Wagon Hill on 6 January 1900 in which Ronald Maclachlan was severely wounded in the chest. He had recovered enough to take part in the action at Laing’s Nek in June and subsequent operations in the Transvaal. In August he was promoted to Captain and saw action at the Battle of Bergendal where, according to The Rifle Brigade Chronicle he ‘did good service with the machine-guns’. The battle, the last set-piece encounter of the war, saw the men of 2nd Rifle Brigade storm formidable Boer positions on top of Bergendal kopje (hill), winning praise from General Buller for their bravery under withering enemy fire. For his services during the South Africa Campaign, Ronald was mentioned in dispatches (Gazette, 24 April 1900) and received the Queen’s Medal with three clasps.

The 2nd Rifle Brigade storm Boer positions at the Battle of Bergendal in August

1900 when Captain Ronald Maclachlan was said to have done ‘good service

with the machine guns’

Meanwhile, Alexander Maclachlan, who had arrived in South Africa on 24 November 1899 with the 3rd KRRC, took part in General Buller’s attempts to relieve Ladysmith, including the fierce fighting at Spion Kop in January 1900. He also saw action in the big push of 12-27 February and was gravely wounded in the fight to capture the final Boer position on Pieter’s Hill. At the end of the war in 1902, Alexander, still only a 2nd Lieutenant, was made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for gallantry. He also received the Queen’s Medal with four clasps, the King’s Medal with two and was mentioned in dispatches.

Meanwhile, Alexander Maclachlan, who had arrived in South Africa on 24 November 1899 with 3rd KRRC, took part in General Buller’s attempts to relieve Ladysmith, including the fierce fighting at Spion Kop in January 1900. He also saw action in the big push of 12-27 February and was wounded in the fight to capture the final Boer position on Pieter’s Hill. At the end of the war in 1902, Alexander, still only a 2nd Lieutenant, was made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for gallantry. He also received the Queen’s Medal with four clasps, the King’s Medal with two and was mentioned in dispatches.

In 1901 or 1902 Captain Ronald Maclachlan returned to 3rd Rifle Brigade in India as Adjutant. In 1904 he served as a transport officer in the Tibet Campaign under Colonel Francis Younghusband. Effectively a military invasion, the Younghusband ‘expedition’ aimed to stem what was perceived as growing Russian influence in the semi-autonomous state which was nominally under Chinese protection. The Tibetan army resisted fiercely but its troops, overwhelmingly peasants, were no match for the British. The harsh terms of the resulting treaty outraged many influential Britons and in 1906 Anglo-Tibetan relations were renegotiated, with China agreeing not to let any other foreign state interfere in Tibet. Britain for its part promised to keep out and not interfere in Tibetan matters. Ronald Maclachlan received the Tibet Campaign Medal with clasp.

Back in England, Ronald’s mother was by 1901 living at 8, Rockstone Place, his grandparents’ old home. Two of Ronald’s sisters, Eveleen and Elsie, were living with her, together, presumably, with his mentally handicapped brother, Ivor. The Rev. Archibald Maclachlan was still at The Vicarage in Newton Valence, together with his eldest sister Mary Abigail. This was not an uncommon situation at that time: an unmarried sister who did not need to work would keep house for her unmarried brother. By 1903 Mary Maclachlan had returned to Newton Valence, her address in Kelly’s Hants & IOW Directory being given simply as ‘the Village’. Elsie Maclachlan died on 15 May the same year, aged 33. Like her brother Lachlan, Elsie has a lancet window dedicated to her by her family in Newton Valence church while the altar cross was paid for by friends in her memory.

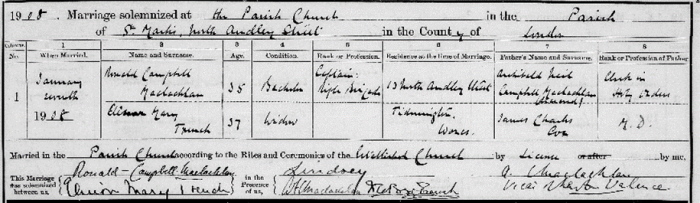

Ronald Maclachlan and Elinor Trench’s marriage certificate from 7 January 1908

On 7 January 1908 Captain Ronald Maclachlan, then aged 35, married Elinor Mary Trench, a 37-year-old widow at St Mark’s Church, North Audley Street, London. His brother Archibald conducted the service. On the marriage certificate, Ronald’s address was given as 13, North Audley Street and Elinor’s as Tidmington, Worcestershire. The daughter of James Charles Cox, a well-known doctor and scientist, and his first wife, Margaret, Elinor had been born in Australia in about 1871. She married William Le Poer Trench in London in 1891 and they had one daughter, Beth, born in Sydney, Australia, in about 1902. William died in Eton, Berkshire in 1904, aged 37.

A few weeks after the wedding, on February 1, Ronald was appointed Adjutant of Volunteers and six months later was made Adjutant of the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) at Oxford University. In between the two appointments, however, came the news that his brother Neil had been accidentally killed while on active service in India with the 1st Seaforth Highlanders. We know nothing about the circumstances of the accident except that it happened while Neil, aged 43, was taking part in the Mohmund Campaign against ‘rebels’ on the North West Frontier.

Ronald held the post of OTC Adjutant at Oxford until 30 September 1911 and was responsible for its evolution from the old University Rifle Corps. In his history of The Rifle Brigade 1914-18, William Seymour states: ‘So successful was he [Ronald] that, though his own personality, the somewhat unpopular “dog shooters” gave place to a body of enthusiasts with a waiting list containing the best men in the University…’ He was promoted to Major in January 1910 and at the end of his appointment the university awarded Ronald an Honorary MA Degree in recognition of his work.

The 1911 Census showed that he and Elinor, together with her daughter Beth, were living at Elmthorpe, a 17-room property on Oxford Road, Cowley, then a prosperous, leafy suburb. The census also revealed that Ronald’s mother Mary, aged 76, had moved to The Cottage in East Tisted, close to Newton Valence. Although she employed several servants, the only family member living with her was her youngest son Ivor, 33. Her daughter Eveleen, who had been with her in 1901, was by then living with her brother Archibald and sister Mary at The Vicarage in Newton Valence.

At the end of his posting in Oxford Ronald returned to his regiment and gained promotion to Colonel. The next phase of his career is somewhat unclear. According to his obituary in The Times in August 1917 (and re-published in The Hampshire Chronicle a few days later), he moved to Winchester with Elinor in around May 1914, apparently to take up command of the Rifle Brigade Depot. The obituary stated that the couple took up residence in their new home, Langhouse, in Chilbolton Avenue, Weeke (the house no longer stands).

Great War Record

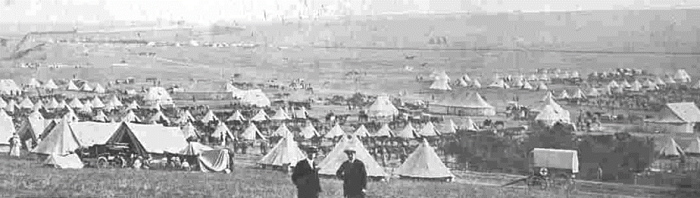

However, Ronald never became Depot commander. Instead, in June 1914, he was appointed Colonel of the Oxford University OTC and over the following three months he trained 500 officers, mainly at the Churn Camp on the Berkshire Downs. According to William Seymour: ‘When war came in 1914 it was thanks to Maclachlan at Oxford … that the Regiment obtained such a magnificent band of young officers.’

Churn Army Camp on the Berkshire Downs in 1914 or 1915 where Ronald

Maclachlan trained men of the Oxford University OTC

Shortly after the outbreak of war, Ronald took command of the newly-formed 8th (Service) Battalion, The Rifle Brigade. Formed at Winchester on 21 August 1914 as part of Lord Kitchener’s First New Army, the battalion joined 41st Brigade in 14th (Light) Division. Under Ronald’s guidance, these volunteers trained initially at Aldershot before moving to Grayshott, near Haslemere, Hampshire, and then returning to Aldershot in March 1915 for final training. They then proceeded to France, landing at Boulogne on 19 May.

The 8th Rifle Brigade first saw action on 5 July but its real baptism of fire – literally - came at the end of the month. On 19 July, the British exploded a large mine under German trenches at Hooge, a small village about two miles east of Ypres in Flanders. The blast left a crater some 120ft wide and 20ft deep with a lip 15ft high which British troops immediately occupied. German retaliation came on 30 July. The British 41st Brigade had taken over the line just a week earlier with 8th Rifle Brigade holding the lip of the crater. At around 3.15am a devastating enemy artillery and machine gun barrage opened up and hissing jets of flame shot across from the German trenches. It marked the first use of flamethrowers in warfare against the British and the weapon spread terror and consternation among the troops of 8th Rifle Brigade. An officer of a battalion occupying neighbouring trenches described the scene:

[T]he Bosch attacked our right flank held by R. Maclachlan’s battalion (8th) and drove them out with liquid fire. It was just at dawn when suddenly flares and star shells arose all together and then the horrible fire jets which look just like a fire hose, except they are fire instead of water. After a couple of minutes of this up went the Bosch red rockets, the signal for their artillery, and from that moment till Monday night, about four days, we lived through continuous bombardments day and night.

One company of around 200 men was virtually obliterated early in the attack. Other men fled their trenches and were either picked off by machine guns or pulverised by artillery as they sought the sanctuary of the support trenches. Many of those who remained in the front trenches died in hand-to-hand fighting with German troops and virtually all the forward positions held by 41st Brigade had to be abandoned. Ordered to counterattack the same afternoon, 8th Rifle Brigade suffered more casualties in a futile assault on the Germans now dug in at the crater. The day’s fighting cost the battalion 19 officers and 469 other ranks killed, wounded and missing. Shortly afterwards, Ronald wrote to the parents of an officer killed in what quickly became known as the Hooge Liquid Fire Attack:

It is a cruel story: it was a sudden attack under cover of liquid gases that set the trench aflame. In spite of all the horror and confusion, your boy, apparently with two other officers … rallied the men at once and firing hard through the flames, held their ground. It was simply heroic and just what we all knew could and would be done by your boy in a tight corner.

Contrary to what Ronald Maclachlan’s obituary in The Times stated, he is not believed to have been wounded at Hooge. Rather, he survived unscathed only to be severely wounded on 29 December 1915 while serving with his battalion near Ypres. Nothing is known about how he received the wounds which were serious enough to put him out action for nine months. Ronald would have been evacuated to England for treatment, so he almost certainly spent time with his family in Winchester. On 3 June 1916, while still recuperating, Ronald received the DSO for distinguished service in the field.

Ronald resumed command of 8th Rifle Brigade on 23 September 1916 during the Somme Offensive. The battalion had just taken part in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (12-17 September), one of the most successful British attacks of the campaign. However, it also proved to be its last action there and in mid-December the battalion, together with the rest of 14th Division, moved north to trenches near Arras.

On 30 December 1916 Ronald Maclachlan was mentioned in dispatches. Then, just a week later, his 23-year association with the Rifle Brigade came to an end when he was promoted to Brigadier-General, commanding 112th Infantry Brigade in 34th Division. The appointment was clearly sudden because Ronald did not even have time to say farewell in person to his battalion. Instead, he wrote a short note in pencil on a sheet torn from his field message book which was then read out to his assembled men at a special parade. In it, Ronald spoke of his pride at having commanded the battalion for so long and of its ‘splendid spirit’ despite ‘constant fighting and incessant losses’

The battalion’s response, also read out, demonstrated the respect and deep affection that the men felt for their Commanding Officer:

The Battalion wish to express what a lasting debt they owe to you for the skill, energy and devotion with which you have trained and nursed them in their early days and led them and inspired them in active service. We feel that any success that has fallen to the Battalion has been founded on your example and leadership. Those who have served under you will never forget what you have done for them and will strive to pass on the high tradition of the Regiment which you have established in the 8th Battalion. All ranks unite in wishing you happiness and highest success in your new command and in any higher post to which you may be called.

Ronald’s promotion put him on the Army’s General Staff with responsibility for some 4,000 men in four battalions, plus support troops. In April 1917 he commanded 112th Brigade during first three phases of the Arras Offensive (9 April-16 May) and his inspirational leadership was a key factor in the capture of the village of Monchy-le-Preux during the First Battle of the Scarpe (9-14 April). Major-General Hugh Bruce-Williams, commander of 37th Division, wrote later:

We wondered how it was possible for the Germans to have let his [Ronald’s] men get to the summit of the ridge where there was not a blade of cover. It was his personal example and personal influence only that did it. He was right up at the front, almost in the front line.

With the end of the fighting at Arras, 37th Division moved north to Flanders. The 112th Brigade did not figure in the start of the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) which began on 31 July 1917, but it did subsequently take over a stretch of line between Bee Farm and Forret Farm, near Hollebeke, south-east of Ypres.

In reality this ‘line’ consisted of a stretch of shell holes with little cover and the Brigade War Diary noted ominously on 7 August that enemy snipers were harassing troops trying to make their way to the front. It proved a tragically prescient observation. Four days later, as Ronald Maclachlan made an early morning visit to the line, he was shot and killed by a German sniper. He was 45 years old. His obituary in The Times stated that he had attended a senior officers’ course in England just three weeks before his death and one wonders whether he took the opportunity to visit his family in Winchester for what would have been the last time.

Brigadier-General Ronald Maclachlan’s grave, fourth from right, at Locre Hospice Cemetery, Belgium

Ronald, who was posthumously mentioned in dispatches in December 1917, was one of more than one of 78 British and Dominion generals killed in action in the Great War. The fact that he was prepared to put himself in harm’s way endeared Ronald to his men. According to The Rifle Brigade Chronicle 1917, ‘the large number who attended his funeral [on 13 August] was eloquent testimony of the esteem in which he was held by all’. William Seymour wrote:

In the Regiment he was universally beloved: an exceedingly smart adjutant, a good sportsman, a charming companion and a master of his profession, there was no height to which he could not have risen had he been spared. But what distinguished Ronnie Mac above all else was that amazing personality which enabled him to get the best out of all with whom he came into contact. It is unlikely the Regiment will ever again see his equal in character: his superior – never.

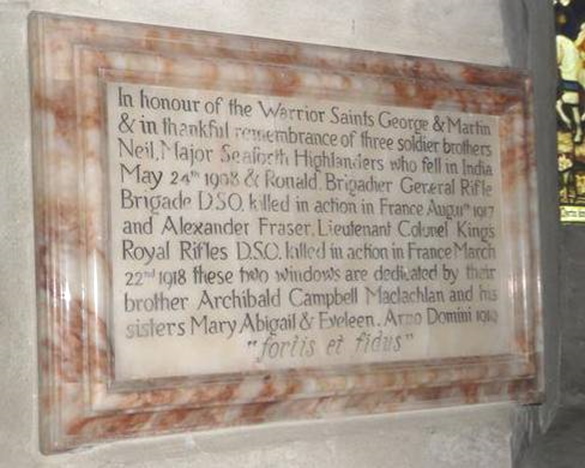

The stone tablet in memory of Ronald, Neil and Alexander Maclachlan. They were

placed in St Mary’s Church, Newton Valence, near Alton, by the

brothers’ surviving siblings

The Glass Window tablet in memory of Ronald, Neil and

Alexander Maclachlan. They were placed in St Mary’s Church,

Newton Valence, near Alton, by the brothers’ surviving siblings

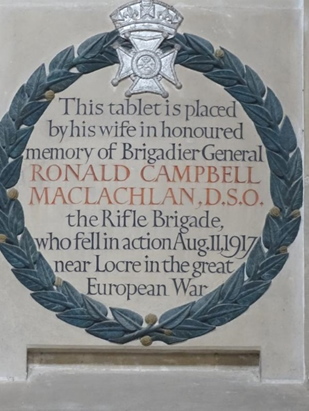

The stone tablet to Ronald in Winchester Cathedral,

placed there by his widow, Elinor

Rookley House, King’s Somborne. Elinor Maclachlan moved here

in about 1920 from the Winchester home she shared with Ronald

The following obituary appeared in The Times on 14 August 1917 and then, four days later, in the Hampshire Chronicle (Page 5):

Brig-Gen R.C. Maclachlan DSO, who fell in France on August 11th, was a son of the late Rev A. Maclachlan, of Newton Valence, Alton, Hants. He was educated at Eton and Sandhurst and joined the Rifle Brigade in 1896. During the South African War, he was mentioned twice in dispatches, was severely wounded and went through the Siege of Ladysmith. He afterwards took part in the Tibet Campaign. In 1908 he became Adjutant of the Oxford University O.T.C., an appointment he held for four years, on giving it up, the honorary degree of M.A., for service rendered to the University. He was very much identified with the Public Schools Camp as Brigade Major.

During the present war he was severely wounded at Hooge on July 30th, 1915, received the D.S.O., and had been twice mentioned in dispatches. He married in 1906 Elinor Mary, daughter of Dr J.C. Cox, of Sydney, NSW. Brig-Gen and Mrs Maclachlan took up their residence in Winchester at Langhouses, Chilbolton Ave about three months before the war started. The gallant officer, who was then a Colonel in the Rifle Brigade, was coming, we believe, in command of the Rifle Depot. On the outbreak of the war he was appointed Colonel of the Oxford University O.T.C. He trained 500 officers at the Chum Camp. After that he trained and commanded one of the new Battalions of the Rifle Brigade and took them to the Front in July 1915.

A brave and conscientious officer, he would never give an order to his men and hesitate to share in the danger of it himself. The men under his command not only respected but invariably beloved him. Death came to him when engaged in a typical action, for he was sniped on the way to the front line trenches. Brig-Gen Maclachlan was in England three weeks ago for a senior officers’ course in the Midlands.

He was one of four soldier brothers. The eldest was an officer in the Seaforth Highlanders, and he met a soldier’s death on the Indian frontier; another brother was accidentally killed while playing in a polo match at Rawal Pindi several years ago; and another brother is an officer in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps on active service (not in France). A brother, the Rev. A.C. Maclachlan, is Vicar of Newton Valence, and is patron of the living. In Winchester, the deepest sympathy will go out to Mrs Maclachlan, who has been such a kindly and devoted worker for the good of soldiers in general and of the Rifle Regiments in particular.

Family after the Great War

For Ronald’s mother, his death must have come as a shattering blow. Further bad news followed on 22 March 1918 when Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Maclachlan, the fourth and last surviving Army brother, was killed in action on the Western Front during the German Spring Offensive. He had been Commanding Officer of 12th Rifle Brigade for just three weeks when, like Ronald, he was shot dead while reconnoitring front-line trenches.

Alexander had enjoyed an illustrious military career. After serving in South Africa, he had been made Captain in 1906 and Adjutant the following year. During King George V’s visit to India in 1911-12 he was appointed an Aide-de-Camp to His Majesty. At home on leave when the Great War began, Alexander was posted to 1st KRRC and took part in the Mons Retreat and the Battle of the Aisne where he was seriously wounded. He rejoined 3rd KRRC in the autumn of 1915 and after being promoted to Major was sent with the battalion to Salonika. In late 1916 he took command of 13th Battalion, The Middlesex Regiment on the Lake Doiran front where, according to the KRRC Chronicle of 1918, ‘he earned further distinction by his example and leadership’. However, the climate affected his health and he was invalided home in the summer of 1917. After being promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel a few months later, he took temporary command of 11th and 12th KRRC before his final posting to 12th Rifle Brigade. During the war he received a Bar to his DSO, the Serbian Order of Kara George with Swords and four mentions in dispatches.

Nor was that the end of the Maclachlans’ misfortune. In late 1918, Ivor, the youngest brother, died at the age of about 40, becoming the sixth of Mary Maclachlan’s nine children to predecease her. Mary appears to have had no grandchildren – her three daughters, together with Ivor and Archibald, never married and there is no evidence that any of the four Army brothers had children. By 1923 Mary had moved back to The Vicarage in Newton Valence where she lived with her three surviving children. She died on 12 June 1925, aged about 92. Her daughter Mary Abigail died in 1941 at the age of 81 and Archibald in 1944, aged 79. Eveleen remained in the Newton Valence area, passing away in 1953, aged 91.

Ronald’s widow, Elinor, devoted herself to the welfare of Rifle Brigade soldiers during the war – her name crops up in several letters in which men remark on parcels - of books, for example – they had received from her. She continued to live at Langhouse immediately following Ronald’s death but by 1920 had moved to Rookley House, Kings Somborne. However, in the Winchester War Service Register of 1921, she gave Ronald’s address as Langhouse, presumably because it was the last one associated with him. By 1925 Elinor had moved again to St Vincents on the Salisbury Road in Upper Clatford, near Andover. She lived there until at least 1937 and died in the Andover area in 1949, aged 79. Nothing is known of what became of her daughter Beth, although she may have returned to Australia.

Medals and Memorials for Ronald Campbell Maclachlan

Brigadier-General Ronald Campbell Maclachlan was buried at Locre Hospice Cemetery, Heuvelland, West Flanders, Belgium (GR. II. C. 9). In addition to the decorations mentioned above, he was entitled to the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. Ronald is remembered on the memorials at St Paul’s and St Matthew’s churches, Winchester. He is commemorated on a stone tablet in Winchester Cathedral, placed there by his wife Elinor, and also on the Rifle Brigade Roll of Honour in the same building. His surviving siblings, Archibald, Mary Abigail and Eveleen dedicated a window and a tablet at St Mary’s Church, Newton Valence, to Ronald and his brothers Alexander and Neil who were also killed on military service. Ronald and Alexander are also listed in the Eton College Memorial Book of those who fought in the Great War.

Additional sources

- William Seymour: The Rifle Brigade 1914-1918, 2 Vols. (London, The Rifle Brigade Club Ltd, 1936).

- The Rifle Brigade Chronicles, 1914, 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1918.

- The King’s Royal Rifle Corps Chronicle 1918.

- Cheam School Archives.

- 112th Brigade War Diary, 1917.