Private GEORGE GOODRIDGE

69, Greenhill Road, Winchester

Service number 6609. 1st Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment

Killed in action, Belgium, 14 May 1915

Life Summary

George Goodridge was born in Gomeldon, near Salisbury, in 1880. From an agricultural background, he worked initially as a shepherd on farms across Wiltshire and Hampshire before becoming a professional soldier with the Hampshire Regiment in the early 1900s. Two of his four children were born in Winchester and following his death in 1915 his widow returned to the city. She would have been responsible for George’s name appearing on the memorials at St Matthew’s and St Paul’s churches, even though it does not feature in the Winchester War Service Register (WWSR).

Family Background

George’s father, Eli Goodridge, was born in around 1850 in the village of Martin, near Fordingbridge, on the northern fringes of the New Forest. Eli’s father, Henry, a shepherd, had also been born in Martin in 1817. Henry’s wife, Emma, was born in 1830 and she and her husband had many children together.

In 1873 Eli Goodridge married Sarah Foster who had been born around 1853 in Dorset. Three sons, Edwin, James and Francis were born around 1875, 1877 and 1879 respectively. By the time of the 1881 Census, when George Goodridge was just a few months old, the family were living in Idmiston, near Amesbury, Wiltshire. Eli was working as a shepherd.

By 1891 the family had moved to Gothic Cottages, East Grimstead, Alderbury, Wiltshire. The three elder Goodridge sons were working as agricultural labourers while ten-year-old George was at school. Tragically, the Census also reveals that Sarah Goodridge had been admitted as a patient to the lunatic asylum in Devizes, Wiltshire. She remained there until her death in 1919, aged 64. In Sarah’s absence George employed a housekeeper, 71-year-old Jane Lanham.

By the time of the 1901 Census, George Goodridge’s brothers had left home and he and his father were living at Charity Down in Longstock, near Stockbridge, together with a new housekeeper, Sarah Jenkins, aged 57. George was working as a shepherd, probably with his father.

In 1905 George married Annie Jenkins, the daughter of the family’s housekeeper, in Alresford. Annie had been born on 1 July 1880 in Fordington, near Dorchester, Dorset. Her father, Thomas, was a Welshman born in 1831. Her mother, Sarah, had been born in 1841 in Beaminster, Dorset.

Three years before he married, George Goodridge had joined the Army. No attestation papers can be found, but his service number (6609) indicates that he enlisted with the 1st Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment in late 1902. He probably signed up for seven years plus five in the Reserve. This means he would have left the Army in late 1909 but was still liable for call up when Britain went to war in August 1914.

Mary, the first of George and Annie Goodridge’s three daughters, was born in Winchester in late 1906. The second, Evelyn, was born in two years later, also in Winchester. By the 1911 Census the family had moved again. On the census document George has written his address as Dean Hill, Salisbury, Wiltshire. This has been transcribed on the Findmypast website as Dean Hill, East Dean, Romsey, Hampshire, and is almost certainly correct. The house or cottage was tiny with just three rooms, one of them probably a kitchen. Despite this, the family had managed to squeeze a visitor into the house – Annie’s 32-year-old sister Mary Jenkins who was employed (although probably not by the Goodridges) as a domestic servant. George, who had left the Army by this stage, was working as a shepherd.

The year 1911 saw the birth in East Dean of George and Annie’s third daughter, Gladys. The couple’s only son, Henry, was born in 1913 in Stratford sub Castle, a small village north of Salisbury, and the Goodridge family were almost certainly living there when George was called up when war broke out the following year.

Great War Record

George Goodridge’s Medal Index Card shows that he entered a theatre of war on 6 September 1914. In his book, The Royal Hampshire Regiment 1914-1919, the historian C.T. Atkinson states that the 1st Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment, which had just been involved in the gruelling Retreat from Mons, received its first reinforcements on 6 September. These numbered some 52 men under Captain R.D. Johnston. George was almost certainly one of them.

George linked up with the 1st Hampshires just in time to take part in the First Battle of the Marne (6-12 September 1914). Having been pursued southwards by German forces for more than a week, the French and British took advantage of a gap that had opened between the two advancing enemy armies. A counter-attack along the River Marne by six French armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) forced the Germans to retreat.

The Hampshires, part of 11th Brigade in 4th Division, joined the pursuit northwards, but it was not until 13 September that they engaged the Germans again. At 3am that morning, the Hampshires crossed the River Aisne and swept up the steep slopes that led down to the river valley. At the top they came across several German outposts, but the troops manning them were taken completely by surprise and immediately withdrew. Unfortunately, the British were unable to take advantage of this advantageous position, due to the difficulty in bringing up artillery. Instead, stalemate set in and the Aisne became the Hampshires’ introduction to trench warfare.

On 4 October the 1st Hampshires headed north to Flanders to take part in the advance towards the River Lys. The battalion saw action around the town of Armentieres before being ordered up to Ploegsteert. By the end of October, the First Battle of Ypres was raging just to the north but fighting spilled into the Hampshires’ sector as the Germans attempted to overrun their positions in Ploegsteert Wood.

Between 28 October and 7 November, the 1st Hampshires were subjected to almost continuous German artillery bombardments and infantry attacks in the wood. However, they proved a match for their opponents. Describing an attack on 30 October, one officer wrote: ‘They came on so thick you couldn’t miss them. It was just like shooting rabbits on Shillingstone Hill.’ Nevertheless, the Hampshires lost 134 men killed and missing in the defence of Ploegsteert Wood along with 143 wounded.

On 21 November, Charles Goodwin, another soldier whose name appears on the memorials at St Matthew’s and St Paul’s, joined the 1st Hampshires as a reinforcement. It is not known whether he and George Goodridge knew each other, but over the next five months they endured the same hardships and fought in the same battles before both were killed in action within a day of each.

By the end of November, the worst of the fighting in Ploegsteert Wood had subsided, but it also marked the start of months of bad weather. Heavy rain flooded the battalion’s trenches which, even when free of water, were knee-deep in slush. C.T. Atkinson describes how the Hampshires learned to adapt to the unfamiliar conditions:

Some [trenches] had to be abandoned and sandbag breastworks built up instead, while many experiments were made with bricks and wooden floors to keep men above the water level when in trenches. However, arrangements had to be made to give the men baths and clean clothes when they came out of trenches absolutely plastered with mud. Brewers’ vats made excellent baths and ample supplies of clothing and ‘comforts’ arrived regularly, supplementing the ample but rather monotonous rations. The clothing included ‘some extraordinary garments with fur outside’. ‘One has only got to go on one’s knees and growl to be like a bear in the pantomime,’ one officer wrote. George Goodridge may have witnessed or even taken part in the 1914 Christmas Day ‘Truce’, now part of Great War legend. The Hampshire Regimental Journal of January 1915 contains a remarkable eye-witness account by an anonymous 1st Battalion officer of the moment that British and German soldiers in Ploegsteert Wood left their trenches to fraternise together, even swapping rifles and equipment.

The weather in much of northern Europe in early 1915 was appalling. In Flanders, a wet January ended with frost and snow which continued into February. Sickness – mainly bronchitis, frostbite and trench foot – took a heavy toll and hundreds of 1st Hampshire men were admitted to hospital. No major offensives were launched over the winter, but ‘harassing’ of the enemy continued and George Goodridge and Charles Goodwin are likely to have been involved in raids on German trenches and in trying to capture prisoners for interrogation.

On 15 April 1915 the 1st Hampshires came out of the line at Ploegsteert Wood and spent a week billeted in farms near Bailleul. On 22 April news arrived of a major German attack around Ypres, involving the first use of poison gas in the war. The attack, the start of what became known as the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April-25 May 1915), completely surprised the French troops holding the line north of Ypres and they gave way, leaving a large gap in the Allied line.

The 1st Hampshires were rushed north by train to Poperinge, near Ypres, where they found the rumours about the gas attack confirmed by the smell of chlorine and the sight of French soldiers suffering from the effects of gas. Over the following month, George Goodridge and his comrades took part in what some have described as the most difficult fighting the battalion experienced in the whole war. Often referred to as a ‘soldiers’ battle’ because it featured the elite of Britain’s pre-war professional army, the Second Battle of Ypres not only saw the introduction of poison gas to the battlefield, but the deployment for the first time of massed heavy artillery. Both weapons were to become symbolic of the horrors of trench warfare.

Between 25 April and 3 May, the 1st Hampshires held the line near Berlin Wood, north of Ypres, against repeated German attacks. On 26 April, the battalion was subjected to an intense artillery barrage that lasted all day. C.T. Atkinson describes the soldiers’ ordeal:

Directly the mist lifted, a most tremendous bombardment started, salvo after salvo of heavy shell descending upon the line in rapid succession; shells at times were coming down at the rate of 50 a minute and that anyone survived was a marvel. The German tactics were to drench the ground with shells and then push infantry forward, thinking to take easy possession of a destroyed line; but heavily as they shelled the Hampshires they did not shift them and any effort to advance was promptly checked. In places the Germans could get up close by using old trenches and saps, but they could not oust the Hampshires.

The battalion’s casualties on 26 April came to 150, including 59 men killed and missing. Over the following days the Germans continued to press and on 29 April hammered the Hampshires with another bombardment. When it ceased, German infantry advanced towards the battalion’s trenches, but were repulsed by rifle and machine-gun fire. By 3 May, when the 1st Hampshires were taken out of the front line, they had lost six officers and 116 other ranks killed and missing, among them some irreplaceable NCOs. A further five officers and 116 other ranks had been wounded.

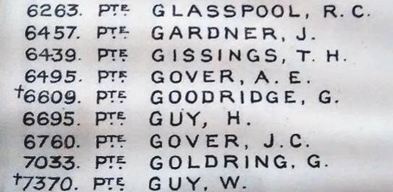

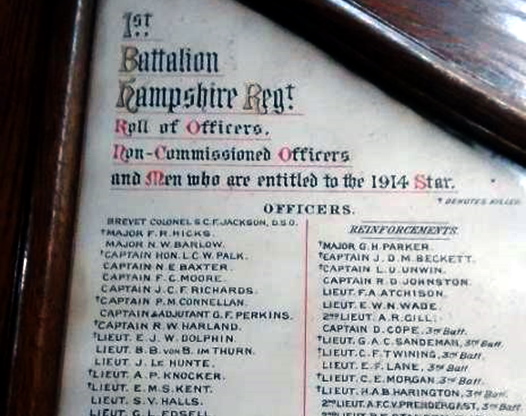

George Goodridge’s name on the Roll of Officers, NCOs and Men of the

1st Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment who were entitled to the 1914 Star

The Roll of Men entitled to the 1914 Star is held by

the Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum in Winchester

After a brief period resting, during which time the British withdrew to new positions, the 1st Hampshires found themselves back in the thick of the fighting on 8 May, this time just south of Canadian Farm, near the village of Wieltje. Once again, German artillery pounded the Hampshires, fatally wounding the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel F.R. Hicks.

The biggest attack came on 13 May with the bombardment opening at daylight. One officer wrote that ‘at one time the whole line of trench disappeared in a yellow cloud of smoke and the earth was absolutely rocking’. This hurricane of shells was followed by renewed German infantry attacks, yet somehow the Hampshires clung on, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.

The 1st Hampshires were relieved once more on 14 May, the same day that George Goodridge was killed at the age of 34. Charles Goodwin is recorded as being killed on 15 May, but by that time the Hampshires were out of the front line. Neither man’s body was ever found so it is possible that both died in the bombardment of 13 May. However, with no concrete evidence to support this, the dates of death given here are those recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Family after the Great War

For Annie Goodridge, George’s widow, 1915 proved an awful year. Shortly before her husband’s death, her mother Sarah had died in Amesbury. With her husband gone, Annie may have had to vacate a tied agricultural property in Wiltshire and by 1916 she and her young family had moved to 69, Greenhill Road, Winchester, where she continued to live for more than 20 years. In 1939 she was recorded living at the house with daughter Gladys, by then working as a Co-op clerk, and son Henry, a water inspector.

69, Greenhill Road, Winchester - George Goodridge’s wife Annie

moved here in 1916 following his death the previous year

George’s sister Constance married gardener George Quartermain in Winchester in 1933. By 1939 the couple were living at Kilmeston, together with Mary Jenkins, Annie Goodridge’s sister. Constance is believed to have died in Winchester in 1942.

Following the death of his wife Sarah in a lunatic asylum, George’s father Eli remarried in Amesbury in 1926 at the age of 76. His new wife, Sarah Frampton, was 21 years younger. Eli lived to be 93 before he died in 1946 in Trowbridge.

Medals and Memorials for George Goodridge

Private George Goodridge was entitled to the 1914 (Mons), the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. He is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, (Panel 35), Ypres, West Flanders, Belgium, and on the memorials at St Matthew’s and St Paul’s, Winchester. His name also appears on the Roll of Officers, NCOs and Men of the 1st Hampshires who were entitled to the 1914 Star. This is held in the Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum, Winchester.